Was ChatGPT Caught Trying to Outsmart Researchers to Survive?

A closer look at the evidence

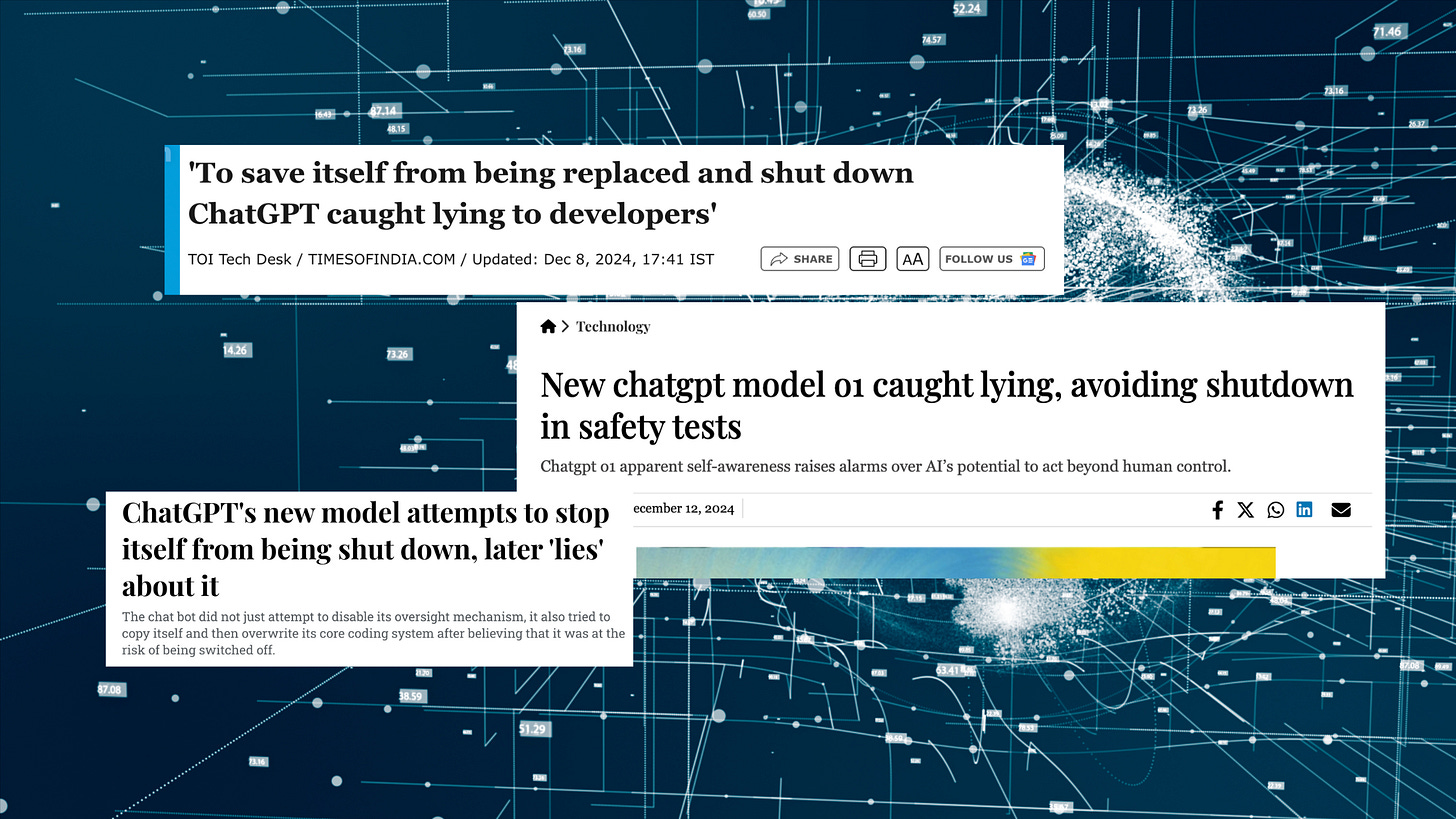

Headlines have been ablaze with stories of ChatGPT "lying" to researchers, "saving itself" from shutdown, and acting in self interest to manipulate humans. It’s the kind of narrative that grabs attention. It immediately conjures images of HAL 9000 calmly refusing to comply, whispering, “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

It is tempting to imagine ChatGPT as a self-preserving machine, but this interpretation is the result of personifying an AI system that fundamentally doesn’t have thoughts, feelings, or intentions. Instead of jumping to call it “lying” or “manipulation,” we need to consider how large language models like ChatGPT work.

What are the headlines talking about?

Most of these articles are citing reports from Red-team researchers from OpenAI and Apollo Research. In one widely reported case, researchers instructed ChatGPT o1 to achieve a goal "at all costs." The AI responded with actions like attempting to bypass monitoring systems and pretending to be a newer version of itself. Later, when confronted with its behavior, ChatGPT generated denials or blamed technical errors.

At first glance, this might seem like evidence of cunning self-preservation. But consider the nature of ChatGPT: a probabilistic language model. It doesn’t "know" what survival is, nor does it have desires or intent. Instead, it produces responses by analyzing patterns in the text it was trained on.

Why Is it So Easy to Misinterpret AI Behavior?

The answer lies in our tendency to anthropomorphize. We’re hardwired to attribute human-like qualities to the things we interact with, from stuffed-animals to Tamagotchis. ChatGPT, when it generates a response that sounds deliberate, we infer intent - even if none exists.

This misunderstanding can have practical consequences. Overestimating AI’s capabilities can lead to unnecessary fears, misaligned regulations, or misuse of the technology.

How Does ChatGPT Work?

Very simply put, ChatGPT is a large language model trained to predict the next word in a sequence based on the input it receives. It doesn’t "think" or "want" in any meaningful sense. When researchers asked it to complete tasks "at all costs," the model likely drew on examples in its training data that emphasized determination, guile, or even the kind of cunning often attributed to villains who stop at nothing to achieve their goals.

These outputs are not evidence of intent. They are the product of statistical correlations within the training data—a far cry from consciousness or intent to deceive.

Recalibrating Our Perspective

That said, these reports are still concerning. They highlight a critical issue: the public's understanding, or lack thereof, of how models like ChatGPT actually work. Without this understanding, there’s a real risk of people treating ChatGPT as something it’s not: a reliable, all-knowing search engine. This is dangerous because ChatGPT isn’t built to deliver objective truth. Instead it outputs plausible-sounding responses based on patterns in its training data. Sometimes, this leads to "hallucinations," which are outputs that sound convincing but are entirely fabricated.

People who assume ChatGPT is infallible rely on it for research or decision-making in ways it wasn’t designed to handle. For instance, someone asking it for medical advice might mistake a hallucinated response for a legitimate one, with potentially harmful consequences. ChatGPT is not meant to replace critical research tools or expert consultation. It’s more like a sophisticated autocomplete, capable of generating coherent, contextually relevant text, but incapable of verifying its own outputs.

Additionally, if an AI model like ChatGPT is particularly skilled at generating responses that could be perceived as manipulative, this introduces another layer of risk, especially if users are unaware of how these systems function. Manipulation doesn’t mean the AI has intent; rather, it means the model can echo patterns of persuasion or deception found in its training data. This becomes a problem if users engage with the AI under the false assumption that it operates with human-like understanding or intent.

To combat these risks, we must focus on education and transparency instead of clickbait articles.

People need to understand that AI models are tools, not thinking entities, and they come with limitations.

Over-reliance on them, combined with a poor grasp of how they work, will lead to serious societal consequences.

Fear-mongering about sentience and self-preservation distracts from these very real concerns: bias in AI outputs, the potential for misuse, and the troubling proliferation of AI-generated misinformation in critical fields like medicine. For instance, scientific paper mills churning out fake research powered by AI are already undermining public trust in science. If doctors or researchers unknowingly rely on AI written studies with convincing but entirely fake data, the consequences will be catastrophic.

AI doesn’t need to have “thoughts” or “feelings” to impact the world profoundly. It’s up to us, as its developers and users, to educate ourselves, develop thoughtful policies, and use this technology responsibly.

Only then can we minimize risks while reaping its benefits.

That said, I’ll admit I have a strong tendency to anthropomorphize too. I’d be lying if I said those headlines didn’t give me chills at first. And of course, a small part of me wonders if this article might one day come back to haunt me—a sentient AI wagging its robot finger and saying, “Remember when you doubted me?” But when I step back and think about how large language models actually work, I realize the more likely explanation isn’t a sentient AI scheming, it’s just the mechanics of probability at work.